It felt like rain. No, not rain – maybe sleet. It had a bit of a bounce when it hit your skin or clothing. But it wasn’t rain or sleet – the quick accumulation of black particles pointed to something else entirely: the volcano was erupting.

Before we began our driving trip around Sicily, we had spend time in and around Rome, including one day at the remarkable ruins of Pompeii. There, exploring the famed city preserved in time by an unimaginable amount of lava, pumice, and mud, our kids witnessed a history and one of its more horrifying moments. Naturally, they wanted to know if it could happen again – here, now – on the slopes of Vesuvius.

“Sure, but not today,” We reassured them. And, “there is so much more scientific understanding of and monitoring equipment for volcanoes now – we would know it is something if was going to happen.”

Animals are said to have fled Pompeii in the days before its final, massive eruption. Not that pigeons are the world’s most intuitive creatures, but there sure were a lot of them hanging around Pompeii. If something was going to happen, surely the pigeons would panic. And, there were no panicking pigeons today.

The only panic was my own. Remembering from a previous visit to Pompeii that one is its most touted ruins was that of a brothel adorned with images of sexual positions that clients could point to in order to initiate and price the business they were there to conduct (many of whom did not speak the local language), I wondered if our guide would take us there and how she would handle it, knowing there were a number of children in the group.

“To find your way to the brothel, follow the penises!” our guide exclaimed as we navigated the streets towards the famed brothel. “The penis will point you in the right direction!” She chuckled to herself.

The experience had the awkward feeling that came upon you as a kid watching movie with you parents or grandparents when, unexpectedly, a sex scene entered the film. The air stilled, the scene seemed to linger. The awkwardness permeated all.

In Pompeii, beyond the pointing ps and illustrative frescoes of the ruins, our experience was punctuated by the guide’s proclamations of “look to the right just inside the door to see the enormous p!” And, half jokingly, “please don’t touch the enormous p on your way by! That was reserved for Romans who believed it would bring them good luck!” Awkwardly, thus, sex ed, history lessons (though some more legend than lesson), and family adventures became one on the side of a volcano.

Apparently, on the morning of August 24, 79 AD, someone forgot to touch the enormous lucky phallis. For on that day, the ultimate eruption of Vesuvius launched bus-sized boulders, noxious gases, and other volcanic goodies into the air around Pompeii and ended its existence for good. There wasn’t even a word in Latin for volcano at the time of Pompeii’s disruption. The people who lived and visited there simply thought that they existed in the shadow of a mountain – one that occasionally groaned and rumbled, but a mountain, nonetheless. When Vesuvius will erupt again is a subject of much discussion among people who discuss volcanoes, I hear.

So, having learned the horrors of Pompeii’s destruction and proven to the children that there is at least some merit to taphophobia, or the fear of being buried alive, what good, responsible parents wouldn’t take their children near the top of an active volcano for exposure therapy, er, exploratory fun?

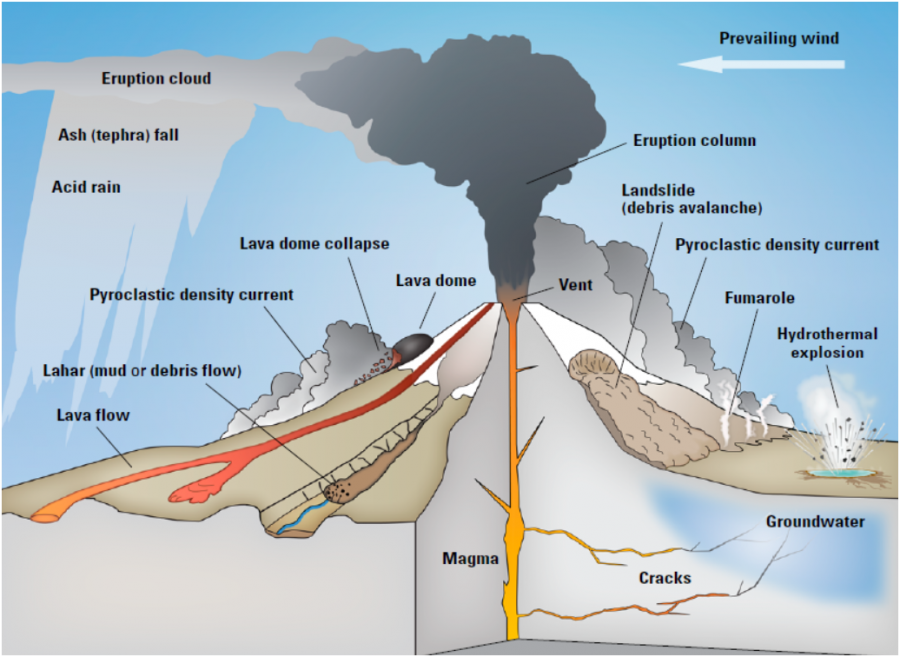

Mount Etna, in northeastern Sicily, is the world’s most active stratovolcano (below) with consistent eruptions for at least 500,000 years. The consistent eruptions and resulting deposits of rich, volcanic soil make the areas surrounding Etna incredibly productive agricultural zones for fruits, vegetables, and, yes, wine. Sicily’s wines are considered the hottest – pun intended – in Italy.

We climbed up, slid down, and explored the accessible cratered areas of Etna at around 6000 foot altitude. Every so often, amidst the exploration of this apocalyptic playground, a kid would ask or give us a look that implied, “this thing ain’t gonna erupt, right?” To which we always replied: nah, it’s not going to erupt – not today! And the play atop Mount Etna continued. A couple members of our party heard a grumble – enough to catch their attention, but not loud enough to catch the attention of everyone.

The next day, it was clear that Etna was no longer playing. That afternoon, the grumbling grew more loud and more regular. Though we were staying in a house more than 40 miles from the Mount Etna playground, the windows rattled between bellows, and the volcanic plumes grew more visible and dark. We continued to reassure the kids – and ourselves – that while this wasn’t routine for us, it was – or, hopefully likely was – for Etna.

The eruption on Etna continued throughout the night (here is some spectacular video footage), providing us with a fireworks display unlike any we had seen around the 4th of July in the past. As we grilled dinner, keeping one eye on Etna, ash rained down onto our heads, clothes, food, and everything else. The feral cats of the neighborhood hung nearby, awaiting gifts of cooked fish and someone reassuring us that, if this eruption really was bad, they would be long gone. I may not trust pigeons, but feral cats? Those things are survivors. Have some more fish, kitten, and thank you for being here with me during this difficult time.

We awoke the next morning to a world covered in a thin layer of black ash. The normalcy of it all – like shoveling snow in wintertime in the Northeast United States – was, perhaps, the most unnerving part of all. Old women swept the sidewalks outside of their front doors, pushing ash into neat piles or into the street. In areas closest to the volcano, the slippery conditions closed roads to bicycles and motorcycles and reduced driving speeds to 30 km per hour ( mph) on highways and main roads. If there had been school, perhaps there would have been an Eruption Delay. Is there a community feed for those events? Nonetheless, people, millions of people, live their lives in the shadow of Etna, relying on the volcano for the abundance it provides while also fearing the existential danger it represents. For us, it added excitement and stories to vacation, for them, it is part of the mysticism of life in Sicily.