The church bells echoed through the quiet town streets of Berat, Albania. It was 6pm, and it was time for giro. We had read about this tradition of “total town promenade” and, honestly, thought little of it. But it was 6 o’clock, and we were sitting by the river drinking Birra Tiranas. “Here they come,” I said, jokingly, as a scattered handful of Berat residents began walking along the river’s edge. I assumed that the giro was an old tradition, guidebook hype, or something that happened only on special, designated days. Not the case.

Picture, for a moment, your fondest – or most horrifying – memory of a middle school roller skating party. The intense awkwardness. The desire to impress. The gawkers and the showboaters – the whole intense, adolescent mess that was the rollerskating rink at that moment. That is giro in Albania, and it happens every night.

At just after the bells tolled six, everyone – and I mean, literally, everyone – in town wandered down to the riverside road (henceforth referred to as the rruga promenada) to promenade. Women are dressed as if going to a cocktail hour or the prom, complete with fresh makeup and styling. Old men don fedoras and jackets while younger ones wear jeans and collared shirts. Young mothers bring their strollered infants, and generations arrive together, all to walk, back and forth, round and around along the rruga promenada. In Berat, this is the place to been seen, and if you’re not seen, people will notice. As teenagers gossip, gawk, flirt awkwardly, and posture, older men plant themselves on brightly-painted benches to watch the waves of residents stroll by. One can imagine the conversations about the weather, town gossip, and how everyone, even Aferdita, looks nicer now than they did under communism. And this goes on for hours, every night, and it’s apparently a critical component of life in Berat.

However, it was difficult to find out what Berat residents thought about the giro. Few Albanians speak any English, and I was met with many a puzzled or agitated glance when I tried to ask questions. Most confusing, perhaps, is the use by many Albanians of a side-to-side nod to signify “yes” and an up-and-down nod for “no.” Other Albanians have adopted the western reverse of these communications, but there is no logic or consistency to whom is using what to say “yes” or “no.” The result: it’s very difficult to communicate in Albania if you don’t speak Albanian.

To make the evening promenade more interesting, the rruga promenada is, like many things in Albania – roads, buildings, democracy – only half-completed. While half of the rruga promenada is newly paved in stone, the other half is just dust and gravel, piles of brick everywhere for the kids to climb on. Further complicating the giro are the man-swallowing holes found in 15 to 20 foot intervals throughout the walkway. Likely sewer or electrical access points, these 2 foot wide by 5 foot deep holes are big enough to swallow an entire promenading family. Lost a sister lately? Haven’t heard from grandma since last week? Check the holes of the rruga promenada! Have extra food? Toss it down a hole of the rruga promenada – you never know what or who might be living there.

Giro route. The pallets (where they exist) cover 5-6ft deep holes.

Giro route. The pallets (where they exist) cover 5-6ft deep holes.

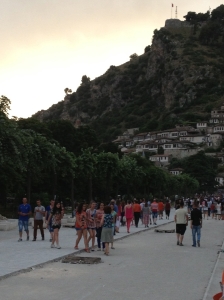

The town is out on the rruga promenada at sundown on a Tuesday.

The town is out on the rruga promenada at sundown on a Tuesday.

Three hours is a long time to parade without music. So…karaoke, anyone? Set atop the stairs of an abandoned communist building at the north end of the rruga promenada, two large speakers and one microphone promised music to giro-goers and opportunity to ambitious or musically-inclined Beratians. With the entire community circling on the street below, young Beratians lined up on the steps for their moment in the spotlight. With 3 to 4 minutes at the mic, and speakers powerful enough to carry music to the entire town, a person could make his mark on the evening’s festivities. I toyed with taking the stage and the opportunity to press myself upon the people of Berat. My performance would stop them in the tracks of their incessant sundown circulation ritual and halt conversations about Grandpa Ardian’s new feathered fedora and Mirjita’s new fish dish. They would notice that a foreigner – an American, no less (few Americans visit Albania) had taken the stage at the Berat sing-a-thon. They would see me there, and when, at the end of my song, I shouted, “should I sing another song?”, the audience would collectively yell something in Albanian and nod their heads. Misinterpreting this sea of nods as a wave of approval, I would begin a second song. They would cut the music, take the mic, and kick me off the makeshift stage. Stunned by what had just happened and gasping for breath in the dust clouds of the rruga promenada, I would stumble into one of the open manholes of the parade route. There, beneath the streets of Berat, I would snuggle up to a stray dog or two and watch the sun set over the mountain town.

Old men in fedoras watch the giro from routeside benches.

Old men in fedoras watch the giro from routeside benches.

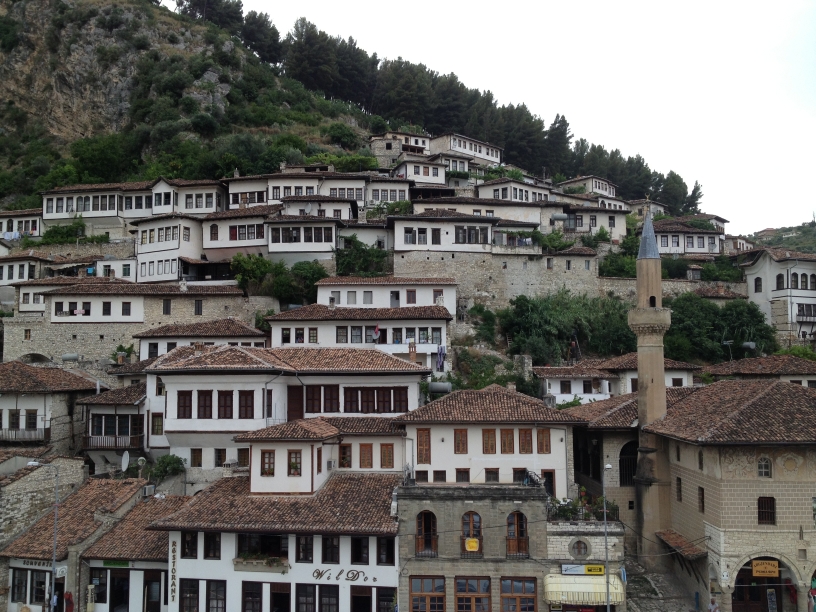

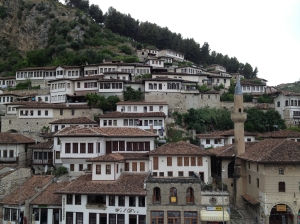

But we had not come to Berat to promenade or sing karaoke. Berat’s hillsides are populated with beautiful Ottoman houses and narrow winding streets that lead up to an ancient fortress. This “city of a thousand windows” is a World Heritage site that is home to some of the only remaining churches and mosques in Albania. Some estimates put the percentage of religious structures destroyed in Albania since World War II at over 95%. How could a country dominated by the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires, two empires dedicated to the promulgation of faith, now be wiped clean of houses of worship?

Enver Hoxha. Considered by many to be among the most brutal and repressive dictators of the 20th Century (now that’s a club that demands impressive credentials!), Hoxha dominated Albanian life for nearly four decades. The Stalinist totalitarian regime he constructed between 1946 and 1985 sought to turn the country into a white-hot mass of unquestioned loyalty to his vision of Albania’s future. Hoxha believed that Stalin had been too tolerant of religion in the Soviet Union and so, in Albania, Hoxha was determined to extinguish religious belief altogether. Religious orders were brought under control of the state, clergy were imprisoned and executed, and, ultimately, virtually all of Albania’s religious buildings were destroyed or turned into storage houses. For some reason, Berat was spared a full cleansing of its religious history.

I was especially excited to visit the fortress atop Berat because it allegedly had an audio tour. In a country with little spoken English and even less in print, this audio tour could provide me with a rare opportunity to get some depth of experience. Even better: there were no tourists in sight – we’d have the place all to ourselves. Jess and I approached the makeshift ticket desk.

“Audio tour, please.”

The man behind the counter shook his head side-to-side. Good! I help up two fingers. “Two, please!”

He again shook his head from side-to-side. Hmmm.

“That’s a ‘no’ nod, not an Albanian ‘yes’ nod,” Jess concluded. “I think there’s no audio tour.”

I was determined to geek-out at Berat castle. I pressed forward. I pointed at the audio tour sign behind the counter. “Audio tour,” I said more slowly and loudly. Because that always works, right?

The man responded with something in Albanian. He looked peeved, and I think he almost stood up to shake me away. He now pretended not to see me.

It was at this moment that we were approached by an Albanian man who had been watching the scene unfold from the nearby castle wall.

“There is no audio tour. It is under repair.” Frustrating, but fitting for a country where everything is seemingly under repair.

“My name is Tony. I can take you on a tour, if you like. I speak English.”

And he did – he probably had the best English we had heard thus far in Albania. Done. We hired Tony for a tour of the castle.

“You want to see the churches?”

“Yes, please. If it’s possible.” I responded.

And with that, Tony walked over to a spot on the castle wall where the keys to millennia-old structures hung on a rusty nail. I had better security on my gym locker at the YMCA than Albania had on its World Heritage site.

We had the castle grounds to ourselves – well, ourselves and the 100 or so people who still live within the walls. Tony is one of them.

“Most of the young people have left for jobs in the city,” he said. “They don’t want to live here, in the castle, and sell souvenirs to the tourists. They want to drive cars and live a different life. There aren’t many of us left here.”

And he was right. Most of the people we saw scattered around the castle were older, some of whom looked as if they may have been there since the Ottomans ruled the land. Most of them sold trinkets, home-spun linens, or worked the few cafes inside the walls. Tony learned his English while serving a 6 month tour for NATO in Afghanistan (Albania joined NATO in 2009) alongside American forces. He also learned Italian just by watching movies as a teenager. I’m always jealous of people who can pick up languages easily. I took Spanish for years and have managed little more with it than getting myself robbed in Argentina. I decided to test out my Albanian on Tony. I had not yet paid him, so he was a captive audience.

“Fall-un-mee-DAY-reet?”

He looked confused.

“Thank you – Faleminderit – Fall-un-mee-DAY-Reeet.” I said it slower and louder. Because slower and louder always works.

“Did I say that right?”

“No.”

He said it and the syllables all blended together. Nicely, perfectly, beautifully.

Why did my version take 10 times longer to say? I tried again.

“FalllllUNmeDAYrit.”

He laughed. “You should watch some Albanian movies. Your Albanian is very bad.”

Oh well. Why were there so many syllables in such a critical word? That just seemed unfair. Where was the expedited version – the Albanian, “thanks”? Maybe I should make that up myself and start a new trend in Albanian linguistics. “Hey, Fallun!” I tried it on Tony. He stopped laughing and continued walking up the hill without even responding.

Tony leads me to one of the castle’s Byzantine churches.

Tony leads me to one of the castle’s Byzantine churches.

Frescos inside the church, protected only by a key hanging on a rusty nail.

Frescos inside the church, protected only by a key hanging on a rusty nail.

It was 5 o’clock, and it was time for a drink. Jess and I chose a rooftop café along the river. From the top, you could see the entire city. We were the only people there. We had two waiters – one who spoke no English, and one who spoke enough to help the four of us navigate a conversation together. We tried to order two beers and ended up with two beers and two plates of meat. Oh well. Faleminderit!

As we enjoyed our drinks and unexpected meat snacks, I noticed something written on the mountain in the distance. The letters were hard to make out because of the afternoon haze, but sure enough, there were letters on the mountain. N-E-V-E-R. Wow, that’s creepy. And odd – in a country where so few people speak English, why was there a very large, very English word on the mountainside? Maybe it was used to terrify the people of Berat into never leaving the city. Perhaps the reason there were still 100 people living in the castle was just that – as children, they had been told tales of what lay beyond the mountain. Horrible tales of Albanian trolls, Dragons, Serbs and other things that may get them if they venture beyond the confines of the town. For generations, children had awakened in the middle of the night terrified by the ghoulish stories of misery and doom they had heard on Ottoman playgrounds and by fireside. Perhaps the nightly promenade was the way of keeping track, taking attendance of the city’s people and ensuring that none had been lost to NEVER Mountain. NEVER had unity and control been so easy! But, wait, why English? And why such big letters, each of which I learned measures in at more than 300 feet high and 150 feet wide?

A hazy day photo, but N-E-V-E-R is evident on the mountainside.

A hazy day photo, but N-E-V-E-R is evident on the mountainside.

Having failed to master a single word of the Albanian language, I turned to the next best resource for answering this question: Google. It turns out that the letters were originally E-N-V-E-R, as in Enver Hoxha, the aforementioned communist dictator. In 1968, a young farmer, Sheme Filja, and a team of locals spent 10 days constructing the five letters as a tribute to Mr. Hoxha. In 1994, in an attempt to remove the now-discredited dictator’s name from the side of the mountain, the Albanian army napalmed it. Now that’s a statement. Filja fixed it. In 2012, Filja and others swapped the E and N (“swapped” makes it sound so easy!) in an apparently revised assessment of Mr. Hoxha’s legacy.

So, it appears that Albanian mothers would have to use other methods to command the obedience of their children. How about forcing tweens to walk with their parents during a community-wide event? Ah, the brilliance of the giro as a tool of social control!

The church bells rang. It was 6 pm. I looked at Jess. It was time for the promenade. “I feel underdressed,” she said. “Me too,” I replied. But our hotel was up the hill, and the parade crowd was already growing.

“There’s the dust,” she said.

“And the holes – we could always fall into one. Tragic to do that in nice clothing.”

“Agreed,” she replied.

“What do you say we have one more drink, and then we hit the streets?”

I motioned to the waiter. He brought two more beers.

“Fallunmeedeerit.” I said with the authority of someone who had quickly finished a big beer on an empty stomach.

He cocked his head and looked confused.

“Thank you,” I said. I smiled and handed him the money.

Informative and humorous as always- I give you my American nod!

Very interesting!!!

I felt like I was there. Love your writing style , humorous yet respectful.